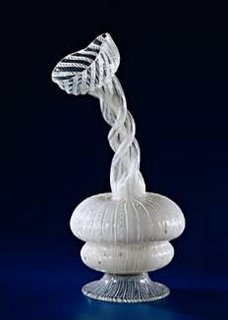

The first half of the 17th century saw a revolution in glassmaking, sparked by the inventions of Venetian craftsmen, who changed the very nature of glassware from a heavy, rigid structure to a frothy magnificence which has never been equaled. The new free-blowing process and the use of soda glass resulted in exquisitely delicate masterpieces like the one shown here. Venetian blown pieces blossomed like airy flowers, the thin walls of goblets and vases glorifiying the intrinsic qualities of the glass itself.

The subject piece is believed to have been commissioned by the Duke of Venice to spare himself and the Duchess the necessity of using outhouses during the long winter nights. Venetian outhouses, unless firmly anchored, tended to move about with the tides, leading to frequent mishaps and the occasional drowning, even among the aristocracy.

A special feature of this particular piece is that liquid moving through the tiny glass tubes at different rates and dripping into the bowl below provides a pleasant selection from Georg Philipp Telemann's Water Music.

Glassworkers in Venice had a relatively short career span. Constant close-up exposure to red-hot glass over the years caused them to eventually lose their sight. Contemporary paintings show these poor wretches in workhouses, where they were taught to assemble the slatted window coverings that have become their only memorial.

(Shamelessly copied from http://www.dearauntnettie.com/gallery/museum-urinal.htm)

No comments:

Post a Comment